To this day, the winds of history are shaping cultures around the globe. Taiwanese art and design are no different. To truly grasp the nature of Taiwanese patterns, it is essential to understand the experiences of people living in Formosa.

The modern identity of Taiwan is a mix of Chinese, Austronesian, Japanese and Western thoughts. Imperialism and colonization had a significant impact on Taiwanese culture and its legacy.

From political upheavals to natural disasters, every brushstroke and architectural detail tells a story of resilience, creativity, and the ever-evolving spirit of the Beautiful Island. Join us on a journey through time as we explore the intricate interplay between history and creativity in Taiwanese art and architecture.

Japanese Imperial Era

Despite that the majority of the Taiwan’s population are descendants of Han Chinese immigrants, Japanese influenced island’s customs, traditions, and artistic expressions.

Japanese were trading in Taiwan for Chinese products long time before the Dutch have arrived in 1624. The first attempt to incorporate Taiwan into Japan failed after naval expedition was dispersed by typhoon.

Two hundred years later, the Ryukyuan ship crashed in the southeastern part of Formosa. Nearly all sailors were killed by aboriginals. Dozen of them found a shelter within the local settlements and then could safely return home. There were about 400 similar shipwreck incidents between 17th and 19th century.

Japan blamed Qing for not ruling Taiwan properly. The Qing Dynasty categorized some aboriginal groups as “barbarians” beyond the reach of Chinese law and culture. This was read by Japan as permission for invasion.

However, they failed again to colonize Taiwanese aboriginals. Kuskus and Mudan tribe fought hard, but had to surrender. After burning all villages and settling large camps, suddenly 600 Japanese soldiers fell terminally ill. Negotiations between Japan and Qing resulted in withdrawal of Japanese soldiers from Taiwan.

The First Sino-Japanese war broke out in 1894 after unsolved dispute over influence in Korea. Qing suffered a crushing defeat and had to comply with Japanese terms.

The Treaty of Shimonoseki from April 1895 imposed on Qing dynasty, among other things, to cede Taiwan and Penghu (Pescadores) Islands to Japan. The era of Japanese occupation left an indelible mark on the island’s cultural landscape. The Japanese introduced significant changes, accompanied by both positive and negative impacts, reshaping Taiwan’s customs, traditions, and artistic expressions.

During the Japanese occupation, which spanned several decades, the island witnessed the implementation of harsh rules intended to enforce Japanese laws. This era was marked by uncertainty as Taiwan grappled with the question of whether it would remain a colony or become a part of Japan.

This pivotal moment marked the beginning of Japan’s efforts to assimilate Taiwanese society into Japanese culture, erasing elements of the island’s national identity through the Kōminka movement. One of the most notable transformations was the mandate for the Taiwanese people to learn the Japanese language, a shift that significantly influenced the linguistic fabric of the island.

However, beneath the surface of these changes lay darker aspects of the occupation. The use of “comfort women” for Japanese soldiers, tragically leading to the suicide of many, remains a painful chapter in Taiwan’s history. Taiwanese individuals were forcibly conscripted to serve in the Japanese army, sometimes even pitted against their Chinese compatriots.

Sentiment to Japan

You might wonder why Taiwanese hold less animosity towards Japan compared to the deep-seated resentment that exists in Korea and mainland China.

Former President Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) said:

Japan transferred sovereignty over Taiwan to the Republic of China (ROC) in October 1945. Some elder people call this ‘Taiwan’s retrocession.’ This was no retrocession. In fact, Taiwan was transferred from the Emperor’s Japanese empire to the one-party rule of the KMT. This was only a switch between two alien regimes. Four hundred years ago, Taiwan belonged to the island’s aborigines. They are the true indigenous people in Taiwan.

Apparently, the events after the 228 incident during the KMT rule have left their mark on Taiwanese society. The White Terror period with introduced martial law initially was repressing communists, but in reality it targeted anyone who criticized the government. The mayor of Wufeng – Gao Yi-Sheng (高一生) – was executed for his advocacy for indigenous autonomy.

Japan invested in the development of the colony. Rice production was improved and many diseases were cured. Thanks to the electrification, new industries such as textiles and chemicals have emerged.

The Japanese government improved sanitary conditions on the island, contributing to decrease of diseases such as cholera and malaria.

Japanese are famous for their punctuality which has seeped into railways in Taiwan. A train is slow in minutes in Taiwanese language, but behind by hours in mainland Mandarin Chinese. This showcases the difference between perception about punctuality in China and in Taiwan.

Unlike the Chinese mainland, Taiwan was never under Communist oppression. It is possible for visitors to witness age-old customs and traditional religious practices that are no longer present on the mainland.

Taiwanese tiles

We can find another captivating aspect of Taiwanese culture in the architectural heritage of the island. One noteworthy feature that adds a touch of charm to old Taiwanese buildings is the use of tiles. Adorned with intricate patterns, Taiwanese tiles create a visual interplay with the humble red brick introduced by Japanese.

Tiles found in Taiwanese buildings not only served aesthetic purposes but also had functional value. The tiles were often used to protect the walls from rainwater and extreme weather, ensuring the longevity of the structures. High seismic activity is another reason to reduce the cost of the outside facades.

This practicality, combined with the artistic flair, made the use of tiles a popular choice among Taiwanese architects and builders.

The combination of tiles and red brick creates a quiet visual dialogue, giving the buildings a unique aesthetic appeal. Using tiles as a finishing touch showcases the attention to detail and craftsmanship that is deeply rooted in Taiwanese culture.

First tiles in Taiwanese architecture emerged with the era of Japanese colonial rule, which lasted from 1895 to 1945. Japan’s cultural and architectural changes in Taiwan had a lasting impact on the island’s built environment.

In Tamsui (淡水, Danshui), there is a fort San Domingo, built by Spanish in 1629. Later in 1642, Dutch captured the fort and upgraded it with stone. The bastion changed name to “Hongmao Castle” (Fort of the Red Heads) after the colorful locks of the Dutch occupants.

In 1867, the British leased the fort and undertook massive renovations, which included the construction of the imposing British Consulate in the eastern section of the fortress compound. Its red brick verandah and red roof tiles complement the color scheme and design of the building.

Inside the consular residence, you can find a high-end colorful Victorian tiles made by Minton Hollins, &Co.

Global circulation of tiles

The journey of tiles is a sweeping saga of culture and craftsmanship, unfurling across centuries and continents. These unassuming clay squares, which today adorn countless thresholds and sacred spaces, hint at stories buried in the sands of time.

Our tale begins in the bustling innovation hubs of the 8th and 9th centuries within the Islamic realms, where artisans meticulously blended their local artistry with Chinese pottery techniques. This fusion birthed a new era of tiles—dense with symbolism and bold in design—gracing the eye with their early flourish of geometric wonders.

Fast forward to the splendor of the 15th century, an epoch when Italian and European royalty fell in love with these ceramic dowries. A tile wasn’t just a tile. It was an emblem of opulence and taste. Lined with the minstrelsy of Venetian style, tiles transformed into necessary decorations across palaces and cathedrals.

As the clock spun its golden hands into the 15th to 17th centuries, nations like Italy, Portugal, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom—witnessed an exuberant period of tile metamorphosis. Artisans danced the delicate ballet between historic motifs and new-age innovation, laying the groundwork for what would become a global staple.

The late 18th century ushered Japan onto the tile manufacturing stage, where the nation ingeniously adapted these clay wonders to echo the esteemed British Victorian style. Japanese tile makers, with their meticulous precision, crafted designs that brought a touch of Victorian elegance to the Far East. They embraced the Victorian aesthetics, interpreting and molding them into something distinctly their own—proving that tiles were not only vessels of tradition but were indeed players in an ongoing dialogue of cultural exchange.

Thus, the global circulation of tiles paints a splendid picture of cooperative creativity. These vibrant squares have wandered through time and terrain, bearing witness to society’s artistic shifts while transforming into expressions of both local and worldly heritages. They remind us of the beautifully tangled web of human ingenuity, a testament to the timeless dance of cultures and the enduring allure of design.

Patterns examples

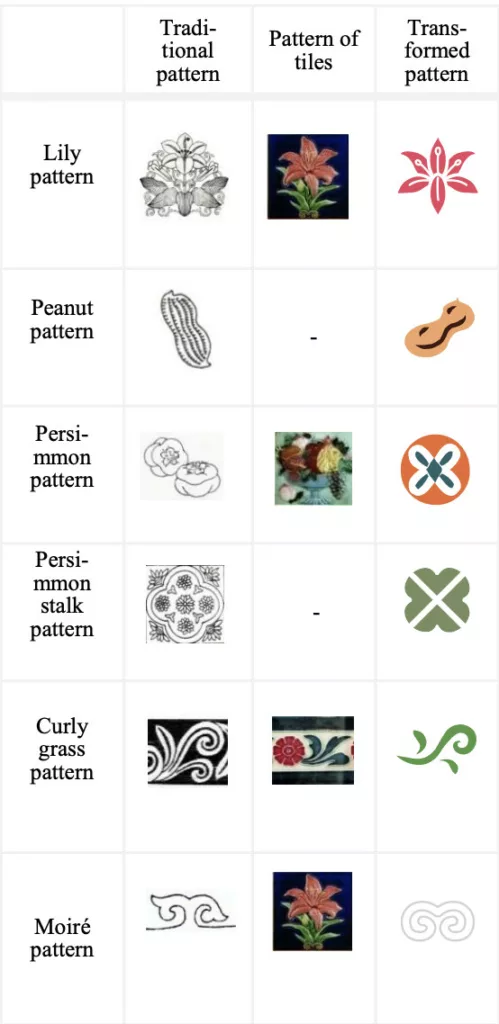

The craftsmanship and patterns of traditional ceramic tiles reflect the beauty of ordinary people’s life in Taiwan.

You can learn more about Taiwanese patterns in the Pan Pan Hua book (爿爿花). It is crowd-funded and won the iF Design Gold Award in 2021.

“爿” sounds “half”, which is an ancient word for “wall”. The tiles are like flowers blooming on the wall. “Fan” and “Piece” are horizontally symmetrical, like a combination of tiles. The meaning of “Fan” as a home also echoes our exploration and discovery of the unique tile mosaics owned by each family.

In Taiwan, there are streets with vibrant murals, a form of street art that has greatly improved the urban landscape of Kaohsiung. The local government of Kaohsiung actively promotes and supports street art by organizing various events and workshops. One notable initiative is the Kaohsiung Street Art Festival, which takes place in different areas of the city, gradually transforming it into a colorful masterpiece. As a result, Kaohsiung has gained recognition as one of the premier cities in Asia for its thriving street art scene.

Architectural changes in Taiwan

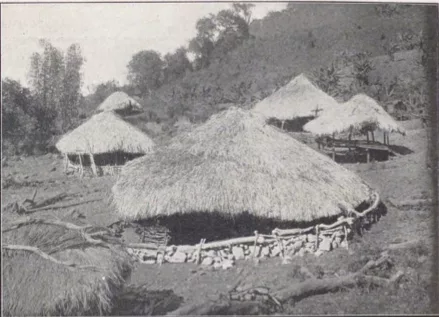

The island’s first inhabitants, in the prehistory period, -1621, left their mark through art forms that reflected their connection with nature, yielding intricate designs inspired by flora and fauna. Aboriginal architecture emerged as a testament to indigenous craftsmanship, integrating natural materials such as bamboo.

The Dutch and Spanish settlements between 1624 and 1662 ushered in a fusion of European aesthetics and local traditions, resulting in a distinct hybrid of design elements. This period was marked by a cross-pollination of styles, leaving behind a visual legacy that’s still visible in Taiwan’s architectural heritage.

The Kingdom of Tungning, from 1662 to 1682, brought a blend of Ming Dynasty architecture with a Taiwanese twist, characterized by elaborate temples and palatial structures. The Qing dynasty, which ruled Taiwan from 1683 to 1896, infused the island with a more imperial Chinese architectural style, leaving behind resplendent temples and ceremonial buildings that grace the landscape to this day.

During the period of Japanese rule, from 1896 to 1945, Taiwan’s architecture was influenced by Japanese aesthetics, featuring minimalist design elements, clean lines, and functional efficiency. The characteristic for that era are red bricks used for the walls material.

Finally, the Republic of China, from 1946 to the present, brought its unique blend of architectural styles, including both traditional Chinese elements and modern influences. Taiwan’s contemporary architecture showcases an exciting juxtaposition of these historical periods, offering a glimpse into its complex and diverse design history. The evolving patterns in Taiwanese architecture tell a captivating story of resilience, adaptation, and cultural fusion that continues to inspire and intrigue designers and admirers worldwide.

Design elements

In Asia, people often decorated bathrooms with calming colors like crisp white, earthy brown, and warm neutrals. These hues create a peaceful and inviting atmosphere that is perfect for relaxation.

At some point, they moved away from the plainness of flat subway tiles, resulting in the emergence of rich shades of purple, yellow, and green.

Symbolism of Taiwanese patterns

Taiwanese artists and designers incorporated traditional patterns into the design of Spring Couplets. Sourcing their inspiration from various artistic and cultural elements. These new designs reflect the uniqueness of Taiwanese culture, rich history and diverse influences. The Chinese calligraphy combined with local motifs and symbols has become an important part of Taiwan’s identity.

People create patterns for a multitude of reasons, driven by cultural and personal motivations. The visual appeal that meets the eye is merely one aspect of patterns. What holds greater significance is the concealed message they convey. Let’s uncover the mystery behind Taiwanese patterns:

of Taiwan Tiles Patterns to Spring Couplets

-

- The lily pattern symbolizes happiness and perfection. Simplified symmetrical structure makes the picture smooth, matching with other elements on Doufang tiles.

-

- The peanut pattern means blessing and continuity. The peanut pattern is simplified to form a smiling face, which is used to decorate the Doufang tiles.

-

- The persimmon pattern symbolizes auspiciousness and good luck. Combined with lilies on the tiles to decorate the Doufang tiles.

-

- The persimmon stalk pattern gives it auspicious meaning. It is flexibly used in the additional space of decorative border tiles, corner tiles, and spring festival couplets.

-

- The curly grass pattern represents wealth. After simplifying its shape and adjusting the curling direction, the pattern integrates into a whole, which is used to decorate the Doufang tiles.

-

- The moiré has auspicious and continuous meanings and is used to decorate the diamond-shaped auxiliary ornaments beside the Doufang tiles in the Spring Festival couplets.